Serotonin is one of the most influential chemical messengers in the human body, affecting everything from emotional well-being to digestive function. Understanding what serotonin is and what it does has become increasingly relevant as researchers uncover its far-reaching effects on physical and mental health. This neurotransmitter, scientifically known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), plays a central role in regulating mood, sleep, appetite, and cognitive functions—making it a critical target for treatments addressing depression, anxiety, and numerous other conditions. The significance of serotonin extends well beyond its popular reputation as the “feel-good” chemical. While low serotonin levels have been linked to depression and mood disorders, this neurotransmitter also influences blood clotting, bone density, sexual function, and gastrointestinal motility.

Approximately 90% of the body’s serotonin resides in the gut, where it regulates intestinal movements, while the remaining 10% is synthesized in the brain, where it modulates neural activity. This dual presence makes serotonin a unique molecule that bridges the gut-brain axis and influences systemic health in ways scientists are only beginning to fully appreciate. By exploring the science behind serotonin—its synthesis, functions, and the factors that influence its levels—readers will gain a comprehensive understanding of how this neurotransmitter shapes daily experience and long-term health. This article examines the biochemistry of serotonin production, its diverse roles throughout the body, the consequences of imbalanced serotonin levels, and evidence-based approaches for supporting healthy serotonin function. Whether seeking to understand the biological basis of mood regulation or looking for practical strategies to optimize brain chemistry, the following sections provide detailed, research-backed information on this essential neurotransmitter.

Table of Contents

- What Is Serotonin and How Does the Brain Produce It?

- The Essential Functions of Serotonin in Mood and Emotion

- Serotonin’s Role Beyond the Brain: Gut Health and Peripheral Functions

- How to Support Healthy Serotonin Levels Naturally

- Serotonin Imbalance: Symptoms, Conditions, and Complications

- The Future of Serotonin Research and Emerging Therapies

- How to Prepare

- How to Apply This

- Expert Tips

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Serotonin and How Does the Brain Produce It?

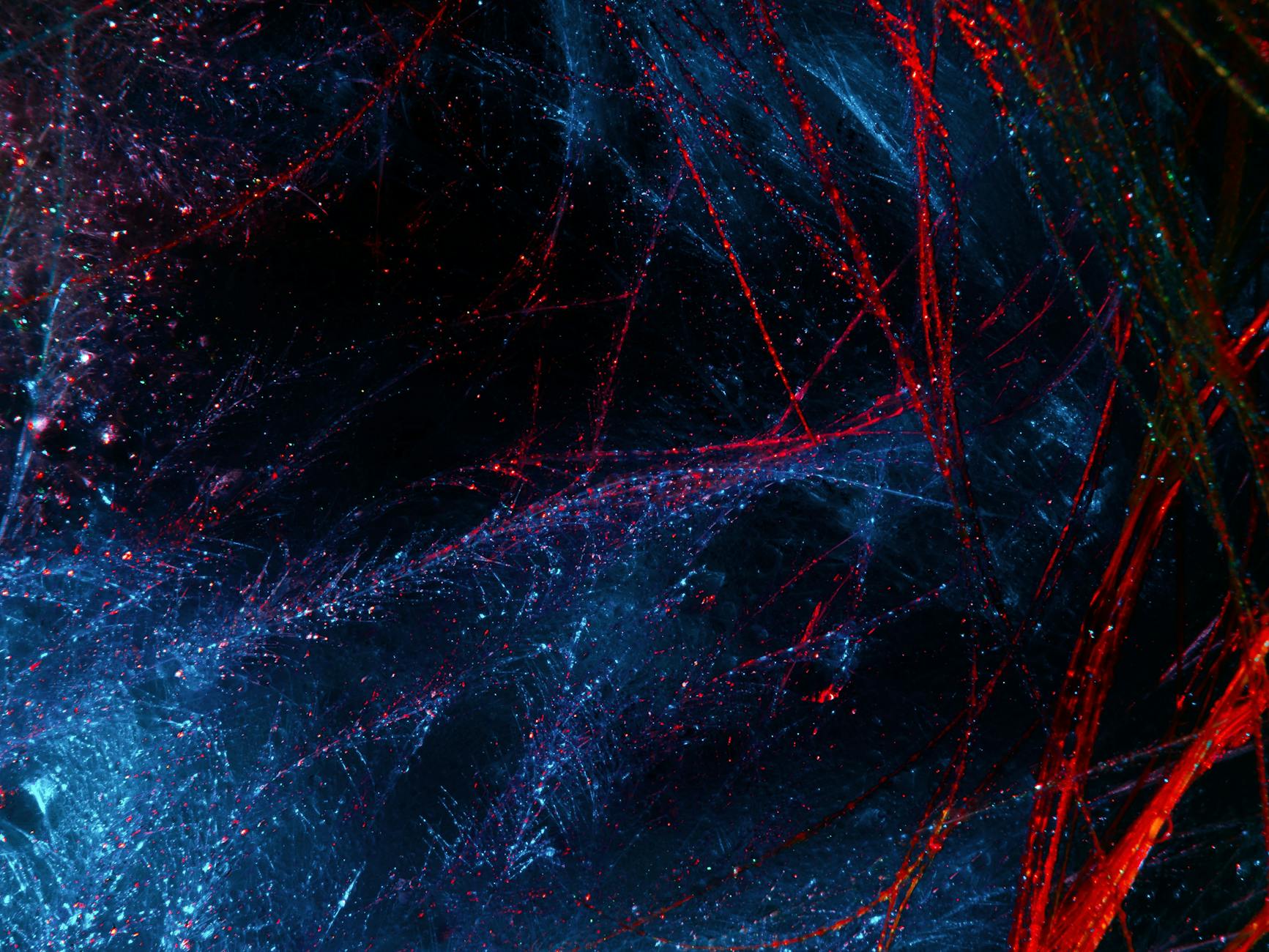

Serotonin is a monoamine neurotransmitter derived from the essential amino acid tryptophan. The synthesis process begins when tryptophan crosses the blood-brain barrier and enters serotonergic neurons, where the enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase converts it to 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP). A second enzyme, aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, then transforms 5-HTP into serotonin. This two-step process is rate-limited by tryptophan hydroxylase, meaning the availability of this enzyme largely determines how much serotonin the brain can produce at any given time.

Once synthesized, serotonin is stored in vesicles within nerve terminals until an electrical signal triggers its release into the synaptic cleft—the small gap between neurons. After release, serotonin binds to receptors on neighboring neurons, initiating a cascade of cellular responses. The signal terminates when serotonin is either broken down by the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO) or reabsorbed into the presynaptic neuron through the serotonin transporter (SERT). This reuptake mechanism is the target of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which block SERT to increase serotonin availability in the synaptic cleft.

- **Tryptophan dependency**: Because the body cannot produce tryptophan, dietary intake directly influences serotonin synthesis capacity

- **Blood-brain barrier selectivity**: Tryptophan competes with other large neutral amino acids for transport across the blood-brain barrier, meaning high-protein meals can paradoxically reduce brain tryptophan levels

- **Regional distribution**: Serotonin-producing neurons are concentrated in the raphe nuclei of the brainstem but project throughout the entire central nervous system, explaining serotonin’s widespread influence on brain function

The Essential Functions of Serotonin in Mood and Emotion

Serotonin’s role in emotional regulation represents one of its most studied and clinically relevant functions. The neurotransmitter modulates activity in brain regions critical for mood processing, including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus. Research using positron emission tomography (PET) scans has demonstrated that individuals with depression often show altered serotonin receptor binding and reduced serotonin transporter density in these regions. The relationship between serotonin and mood is not simply about quantity—receptor sensitivity, distribution, and the balance between different serotonin receptor subtypes all contribute to emotional well-being.

The serotonergic system interacts extensively with other neurotransmitter systems to influence mood. Serotonin modulates dopamine release in reward pathways, influences norepinephrine signaling in arousal circuits, and affects gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity in anxiety-related networks. This interconnectedness explains why serotonin dysfunction can produce such varied emotional symptoms, from the anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure) associated with depression to the hypervigilance characteristic of anxiety disorders. Clinical studies have shown that approximately 60-70% of patients with major depressive disorder respond to medications that enhance serotonin signaling, though the therapeutic effects typically require several weeks to manifest.

- **Receptor diversity**: At least 14 distinct serotonin receptor subtypes have been identified, each mediating different aspects of mood and behavior

- **Circadian influence**: Serotonin levels fluctuate throughout the day and serve as a precursor to melatonin, linking mood regulation to sleep-wake cycles

- **Stress response modulation**: Serotonin helps regulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, influencing how the brain responds to and recovers from stressful experiences

Serotonin’s Role Beyond the Brain: Gut Health and Peripheral Functions

The discovery that the gastrointestinal tract contains approximately 95% of the body’s serotonin fundamentally changed scientific understanding of this neurotransmitter. Enterochromaffin cells lining the gut wall synthesize and release serotonin in response to mechanical and chemical stimuli, regulating peristalsis—the wave-like muscle contractions that move food through the digestive system. This gut-derived serotonin does not cross the blood-brain barrier but profoundly influences digestive health and contributes to conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), where serotonin signaling abnormalities correlate with symptoms of altered motility, pain sensitivity, and visceral hypersensitivity.

Beyond digestion, peripheral serotonin performs several critical physiological functions. Platelets absorb serotonin from the bloodstream and release it at wound sites, where it promotes vasoconstriction and contributes to blood clotting. Serotonin also influences bone metabolism—osteoblasts and osteoclasts express serotonin receptors, and elevated peripheral serotonin levels have been associated with reduced bone density in some studies. Additionally, serotonin affects cardiovascular function, with receptors present throughout the heart and blood vessels mediating effects on heart rate, blood pressure, and vascular tone.

- **Gut-brain communication**: Vagal afferent neurons transmit serotonin-related signals from the gut to the brain, influencing mood, stress responses, and even cognitive function

- **Immune system interactions**: Serotonin receptors on immune cells modulate inflammatory responses, with implications for autoimmune conditions and chronic inflammation

- **Metabolic regulation**: Recent research has identified roles for serotonin in glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and energy balance

How to Support Healthy Serotonin Levels Naturally

Lifestyle factors exert considerable influence over serotonin synthesis and signaling. Regular physical exercise has been consistently shown to increase brain serotonin levels through multiple mechanisms, including enhanced tryptophan transport across the blood-brain barrier and increased expression of tryptophan hydroxylase. Aerobic exercise appears particularly effective, with studies demonstrating that 30-45 minutes of moderate-intensity activity can acutely increase serotonin turnover. Long-term exercise habits are associated with sustained improvements in serotonergic function and reduced risk of mood disorders.

Dietary strategies can optimize the raw materials needed for serotonin production. While tryptophan-rich foods like turkey, eggs, cheese, and nuts provide the amino acid precursor, carbohydrate consumption plays a crucial role in making tryptophan available to the brain. Insulin released in response to carbohydrates drives competing amino acids into muscle tissue, reducing competition for blood-brain barrier transport and effectively increasing brain tryptophan levels. This mechanism may explain the mood-boosting effects many people experience after consuming carbohydrate-rich meals and suggests that balanced macronutrient intake supports optimal serotonin synthesis.

- **Sunlight exposure**: Bright light stimulates serotonin production via retinal pathways, explaining the seasonal patterns of depression seen in regions with limited winter daylight

- **Omega-3 fatty acids**: These essential fats influence serotonin receptor function and may enhance the brain’s sensitivity to serotonin signaling

- **Gut microbiome health**: Intestinal bacteria produce serotonin precursors and modulate gut serotonin synthesis, making probiotic foods and fiber intake relevant to overall serotonin status

Serotonin Imbalance: Symptoms, Conditions, and Complications

Disrupted serotonin signaling has been implicated in a broad spectrum of psychiatric and medical conditions. Depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder all involve alterations in serotonergic function, though the specific nature of these alterations varies across conditions and individuals. Low serotonin activity in certain brain circuits may produce depressive symptoms, while excessive serotonin signaling in other regions contributes to anxiety. This complexity explains why different medications targeting the serotonin system can treat seemingly disparate conditions and why individual responses to serotonergic drugs vary considerably.

Serotonin syndrome represents the dangerous extreme of excessive serotonin activity. This potentially life-threatening condition typically results from drug interactions—most commonly when SSRIs are combined with other serotonergic medications like MAO inhibitors, certain pain medications, or the antibiotic linezolid. Symptoms range from mild (tremor, diarrhea, dilated pupils) to severe (hyperthermia, seizures, cardiovascular instability). Recognition of serotonin syndrome symptoms is critical because the condition requires immediate medical attention and cessation of serotonergic drugs. Cases have increased as prescriptions for serotonergic medications have risen, highlighting the importance of careful medication management.

- **Genetic variations**: Polymorphisms in genes encoding serotonin transporters and receptors influence individual vulnerability to mood disorders and treatment response

- **Hormonal interactions**: Estrogen and progesterone modulate serotonin receptor expression and synthesis, contributing to mood fluctuations across the menstrual cycle and during menopause

- **Chronic illness effects**: Inflammatory conditions, chronic pain syndromes, and metabolic disorders can disrupt serotonin signaling through various mechanisms

The Future of Serotonin Research and Emerging Therapies

Scientific understanding of serotonin continues to evolve as new research tools enable more precise investigation of serotonergic circuits. Optogenetic techniques now allow researchers to selectively activate or inhibit specific serotonin neuron populations, revealing that different subsets of serotonergic neurons mediate distinct behavioral and physiological effects. This granularity challenges the traditional view of serotonin as a monolithic system and suggests that future therapies might target specific serotonin circuits rather than broadly enhancing or inhibiting serotonin throughout the brain.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy represents one of the most significant recent developments in serotonin-based treatment. Compounds like psilocybin and MDMA exert their effects primarily through serotonin receptors, particularly the 5-HT2A subtype. Clinical trials have demonstrated remarkable efficacy for treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, and end-of-life anxiety, with some studies reporting sustained improvements after just one or two dosing sessions. These findings are prompting a fundamental reconsideration of how serotonergic interventions might be used therapeutically and are driving significant investment in research on these compounds.

How to Prepare

- **Assess current dietary tryptophan intake** by reviewing typical food choices and ensuring adequate consumption of protein sources containing this essential amino acid. Foods particularly rich in tryptophan include poultry, eggs, dairy products, nuts, seeds, and legumes. Aim for approximately 250-425 mg of dietary tryptophan daily, which most balanced diets easily provide.

- **Evaluate sleep patterns and circadian rhythm health** since serotonin serves as a precursor to melatonin and plays a central role in sleep-wake cycle regulation. Consistent sleep and wake times, appropriate evening light exposure, and morning sunlight all support robust serotonergic function and circadian alignment.

- **Identify current stress levels and coping mechanisms** because chronic stress depletes serotonin through sustained cortisol elevation and altered receptor expression. Understanding personal stress patterns allows for targeted intervention with evidence-based stress reduction techniques.

- **Review any medications or supplements currently being taken** to understand potential interactions with the serotonin system. Many common drugs affect serotonin signaling, including certain antidepressants, pain medications, migraine treatments, and herbal supplements like St. John’s Wort.

- **Consider gut health status** given the extensive serotonin production occurring in the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms like irregular bowel movements, bloating, or abdominal discomfort may indicate disrupted gut serotonin signaling and warrant attention to digestive health optimization.

How to Apply This

- **Incorporate regular aerobic exercise** of at least 150 minutes per week, as physical activity consistently demonstrates positive effects on serotonin synthesis and receptor sensitivity. Walking, cycling, swimming, and jogging all appear effective when performed at moderate intensity.

- **Structure meals to optimize brain tryptophan availability** by including both protein sources and complex carbohydrates. The carbohydrate-induced insulin response facilitates tryptophan transport into the brain, making the timing and composition of meals relevant to serotonin production.

- **Prioritize morning bright light exposure** for at least 20-30 minutes daily, either through natural sunlight or a 10,000-lux light therapy device. Light exposure through the eyes stimulates serotonergic neurons in the raphe nuclei and entrains healthy circadian rhythms.

- **Implement evidence-based stress reduction practices** such as meditation, deep breathing exercises, or progressive muscle relaxation. These techniques reduce cortisol levels and appear to normalize serotonin receptor function over time with consistent practice.

Expert Tips

- **Time protein and carbohydrate intake strategically**: Consuming a carbohydrate-rich snack 2-3 hours after a protein-containing meal maximizes brain tryptophan uptake by allowing insulin to clear competing amino acids from the bloodstream while dietary tryptophan remains available.

- **Recognize the bidirectional gut-brain relationship**: Addressing digestive symptoms may improve mood, while managing stress can alleviate gastrointestinal complaints. Probiotic supplementation with strains like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium has shown modest effects on both gut function and anxiety symptoms in clinical trials.

- **Avoid self-supplementation with 5-HTP or tryptophan** without medical guidance, particularly when taking any serotonergic medications. These supplements can increase serotonin syndrome risk and may interact with antidepressants, migraine medications, and other common drugs.

- **Understand that caffeine affects serotonin indirectly**: While caffeine does not directly influence serotonin synthesis, it does alter serotonin receptor sensitivity and can affect sleep quality, which subsequently impacts serotonergic function. Limiting caffeine intake to morning hours supports both sleep and serotonin balance.

- **Monitor alcohol consumption carefully**: Although alcohol initially increases serotonin release, chronic use downregulates serotonin receptors and depletes serotonin stores, contributing to the mood disturbances commonly seen with heavy drinking and during alcohol withdrawal.

Conclusion

Serotonin functions as far more than a simple mood molecule—it serves as a critical coordinator of neural activity, gut function, blood clotting, bone metabolism, and numerous other physiological processes. The complexity of the serotonergic system, with its multiple receptor subtypes, regional variations, and interactions with other neurotransmitter systems, explains both its far-reaching influence on health and the challenges inherent in treating serotonin-related disorders. Understanding the fundamentals of serotonin synthesis, signaling, and metabolism provides a foundation for making informed decisions about lifestyle factors that support optimal serotonergic function.

Ongoing research continues to reveal new dimensions of serotonin biology and to develop more precise therapeutic approaches for conditions involving serotonin dysfunction. From the promising results of psychedelic-assisted therapy to the growing appreciation of gut-brain serotonin communication, scientific understanding of this neurotransmitter is advancing rapidly. For individuals seeking to support their own serotonin function, the evidence points toward familiar health fundamentals: regular exercise, balanced nutrition, adequate sleep, stress management, and attention to gut health. These lifestyle factors, while not glamorous, provide the physiological conditions necessary for the serotonergic system to function optimally and support both mental and physical well-being.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it typically take to see results?

Results vary depending on individual circumstances, but most people begin to see meaningful progress within 4-8 weeks of consistent effort. Patience and persistence are key factors in achieving lasting outcomes.

Is this approach suitable for beginners?

Yes, this approach works well for beginners when implemented gradually. Starting with the fundamentals and building up over time leads to better long-term results than trying to do everything at once.

What are the most common mistakes to avoid?

The most common mistakes include rushing the process, skipping foundational steps, and failing to track progress. Taking a methodical approach and learning from both successes and setbacks leads to better outcomes.

How can I measure my progress effectively?

Set specific, measurable goals at the outset and track relevant metrics regularly. Keep a journal or log to document your journey, and periodically review your progress against your initial objectives.

When should I seek professional help?

Consider consulting a professional if you encounter persistent challenges, need specialized expertise, or want to accelerate your progress. Professional guidance can provide valuable insights and help you avoid costly mistakes.

What resources do you recommend for further learning?

Look for reputable sources in the field, including industry publications, expert blogs, and educational courses. Joining communities of practitioners can also provide valuable peer support and knowledge sharing.