Bipolar disorder represents one of the most significant mood conditions affecting the human brain, characterized by dramatic shifts in emotional states, energy levels, and cognitive function that extend far beyond ordinary mood fluctuations. Affecting approximately 2.8% of the adult population in the United States alone, this psychiatric condition creates profound disruptions in daily functioning, relationships, and overall quality of life. Understanding what bipolar disorder is and recognizing its symptoms early can mean the difference between years of undiagnosed suffering and effective management that allows individuals to lead fulfilling, productive lives. The importance of understanding bipolar disorder extends beyond those directly affected.

Family members, friends, employers, and healthcare providers all benefit from recognizing the signs and patterns of this condition. Bipolar disorder frequently goes misdiagnosed or undiagnosed for an average of six to eight years from symptom onset, during which time individuals may struggle with failed treatments, damaged relationships, and declining occupational function. This diagnostic delay often occurs because the depressive episodes of bipolar disorder closely resemble major depression, and hypomanic or manic episodes may be mistaken for personality traits, substance use, or simply “good moods.” By the end of this article, you will understand the neurobiological underpinnings of bipolar disorder, recognize the distinct symptom profiles of manic, hypomanic, and depressive episodes, and learn how different subtypes of the condition manifest. You will also gain practical knowledge about diagnosis, treatment approaches, and strategies for supporting someone with this condition. This comprehensive examination draws from current psychiatric research and clinical practice to provide an accurate, nuanced picture of a condition that affects millions worldwide yet remains widely misunderstood.

Table of Contents

- What Exactly Is Bipolar Disorder and How Does It Affect the Brain?

- Understanding the Symptoms of Manic and Hypomanic Episodes in Bipolar Disorder

- Recognizing Depressive Symptoms in Bipolar Disorder

- How Bipolar Disorder Subtypes Present Different Symptom Patterns

- Common Challenges in Diagnosing Bipolar Disorder Symptoms

- The Relationship Between Bipolar Disorder Symptoms and Cognitive Function

- How to Prepare

- How to Apply This

- Expert Tips

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Exactly Is Bipolar Disorder and How Does It Affect the Brain?

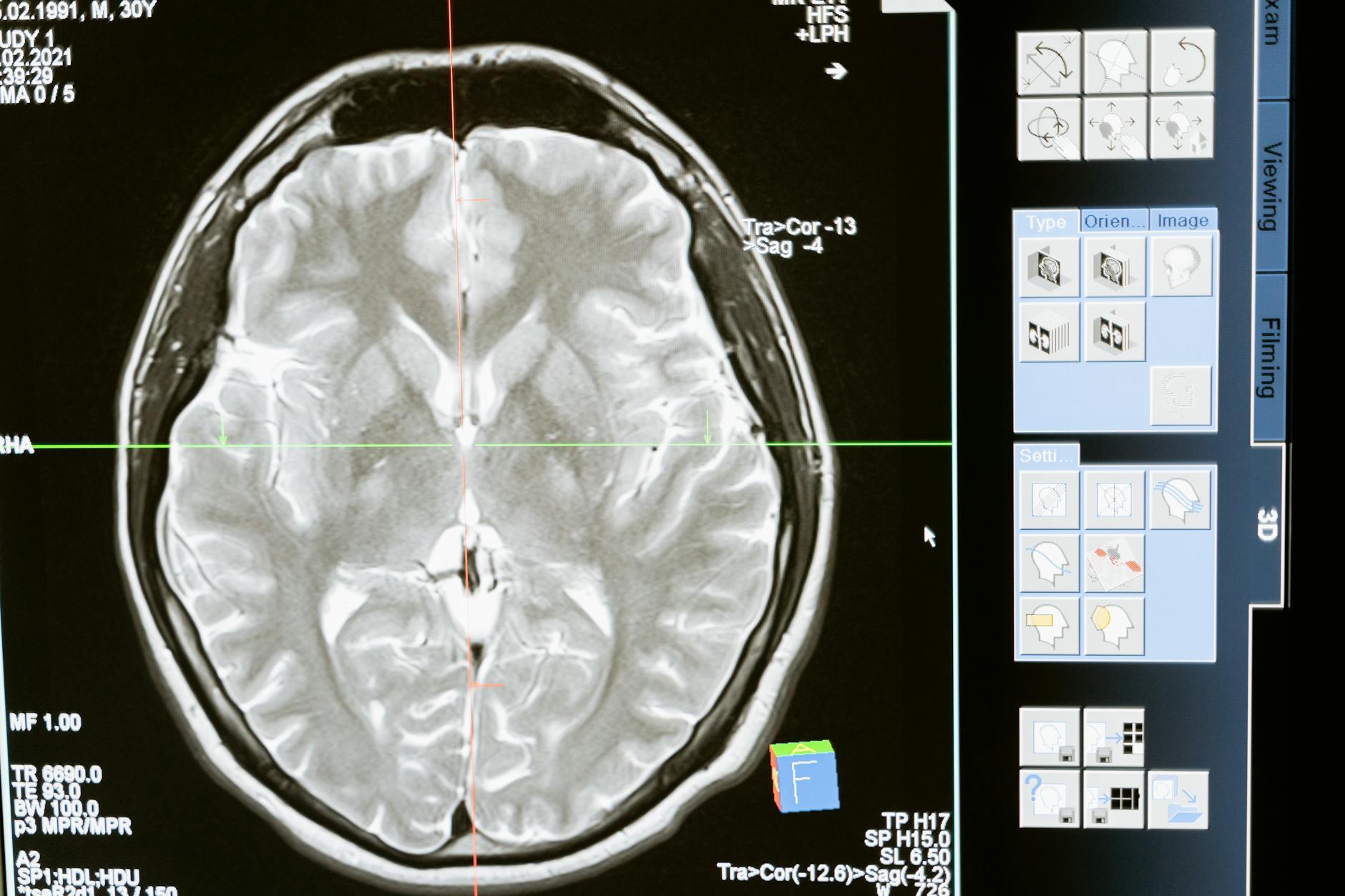

Bipolar disorder is a chronic psychiatric condition classified among mood disorders, fundamentally characterized by episodes of abnormally elevated mood (mania or hypomania) alternating with episodes of depression. Unlike unipolar depression, which involves only depressive states, bipolar disorder cycles between emotional poles””hence the name. The condition arises from complex interactions between genetic predisposition, neurochemical imbalances, and environmental triggers, making it a quintessential example of how biological vulnerability and life circumstances combine to produce mental illness. At the neurobiological level, bipolar disorder involves dysregulation of multiple brain systems.

Research using neuroimaging has revealed structural and functional differences in the brains of individuals with bipolar disorder, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive function, impulse control, and emotional regulation, shows reduced gray matter volume and altered activity patterns in many patients. Meanwhile, the amygdala, which processes emotional stimuli, often demonstrates hyperactivity, particularly during manic phases. Neurotransmitter systems involving dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and glutamate all show disturbances, though the exact mechanisms remain under investigation.

- **Genetic component**: Bipolar disorder has a heritability estimated at 60-85%, meaning genetics play a substantial role in determining who develops the condition. First-degree relatives of individuals with bipolar disorder have a tenfold increased risk compared to the general population.

- **Circadian rhythm disruption**: The condition is intimately connected to the body’s internal clock, with many patients showing abnormalities in sleep-wake cycles, melatonin secretion, and daily energy patterns. Disruptions to regular sleep schedules frequently trigger episodes.

- **Neuroplasticity changes**: Over time, repeated episodes appear to alter brain structure and function, potentially explaining why early intervention and consistent treatment improve long-term outcomes. Each untreated episode may create neurobiological changes that increase vulnerability to future episodes.

Understanding the Symptoms of Manic and Hypomanic Episodes in Bipolar Disorder

Manic episodes represent the defining feature that distinguishes bipolar disorder from other mood conditions. A manic episode involves a distinct period of abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood accompanied by increased goal-directed activity or energy, lasting at least seven days or requiring hospitalization. During mania, individuals experience a dramatic departure from their baseline functioning that is recognizable not only to themselves but typically to others around them as well. The symptom cluster of mania encompasses cognitive, behavioral, and physiological changes that feed upon each other in an escalating pattern.

Individuals may experience racing thoughts that jump rapidly from topic to topic, often described as ideas flowing faster than speech can accommodate. This flight of ideas pairs with pressured speech””talking rapidly, loudly, and with difficulty being interrupted. sleep need decreases dramatically, with some individuals going days with minimal rest yet feeling energized. Grandiosity emerges, ranging from inflated self-confidence to delusional beliefs about special powers, talents, or identity. Risk-taking behavior increases substantially, manifesting as excessive spending, sexual indiscretions, reckless driving, or ill-advised business ventures.

- **Hypomania distinction**: Hypomanic episodes involve the same symptom categories but at reduced intensity, lasting at least four days without causing marked impairment or requiring hospitalization. Hypomania may actually feel pleasant and productive to the individual, making it harder to recognize as pathological.

- **Mixed features**: Some episodes include simultaneous manic and depressive symptoms, creating a particularly distressing state where high energy combines with despair, significantly elevating suicide risk.

- **Psychotic features**: Severe manic episodes may include hallucinations or delusions, typically mood-congruent themes of grandiosity or special purpose, occurring in approximately two-thirds of individuals with Bipolar I disorder at some point.

Recognizing Depressive Symptoms in Bipolar Disorder

The depressive pole of bipolar disorder often receives less attention than manic symptoms, yet individuals with bipolar disorder typically spend far more time in depressive states than in elevated ones. Studies tracking symptom patterns over time found that patients with Bipolar I disorder spent approximately 32% of weeks in depressive states compared to 9% in manic or hypomanic states. For Bipolar II disorder, this imbalance is even more pronounced.

Understanding bipolar depression is therefore essential for recognizing and managing the condition effectively. Depressive episodes in bipolar disorder share many features with major depressive disorder but also display some characteristic differences. Common symptoms include persistent sad, empty, or hopeless mood; loss of interest or pleasure in activities previously enjoyed; changes in appetite and weight; sleep disturbances (either insomnia or hypersomnia); psychomotor agitation or retardation; fatigue and loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt; difficulty concentrating or making decisions; and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide. The subjective experience often involves a sense of heaviness, slowing, and disconnection from life’s meaning.

- **Atypical features**: Bipolar depression more commonly presents with atypical features such as hypersomnia (sleeping excessively), increased appetite, leaden paralysis (heavy feeling in limbs), and mood reactivity (mood brightens temporarily in response to positive events).

- **Earlier age of onset**: Bipolar depression typically begins earlier in life than unipolar depression, with most cases emerging in the late teens to mid-twenties.

- **Episode characteristics**: Depressive episodes in bipolar disorder may be shorter in duration but recur more frequently than in major depressive disorder, and they show higher rates of psychotic features.

How Bipolar Disorder Subtypes Present Different Symptom Patterns

The diagnostic classification of bipolar disorder recognizes several distinct subtypes, each with its own symptom profile and clinical course. Understanding these subtypes helps explain why bipolar disorder manifests so differently across individuals and guides treatment selection. The primary categories in the current diagnostic system include Bipolar I Disorder, Bipolar II Disorder, Cyclothymic Disorder, and other specified and unspecified bipolar-related disorders. Bipolar I Disorder requires at least one lifetime manic episode meeting full criteria, though most individuals with this diagnosis also experience depressive episodes.

This subtype typically involves the most severe symptom presentations, with manic episodes that may require hospitalization and cause significant life disruption. The lifetime risk of psychotic symptoms is highest in this group. Bipolar II Disorder, by contrast, is defined by at least one hypomanic episode and at least one major depressive episode, with no history of full manic episodes. Though sometimes perceived as a “milder” form, Bipolar II often carries significant burden due to the predominance of depressive symptoms and associated impairment.

- **Cyclothymic Disorder**: This condition involves chronic, fluctuating mood disturbance with numerous periods of hypomanic and depressive symptoms that do not meet full episode criteria. Symptoms persist for at least two years and cause clinically significant distress or impairment.

- **Rapid cycling**: Approximately 10-20% of individuals with bipolar disorder experience rapid cycling, defined as four or more mood episodes within a twelve-month period. This pattern is associated with earlier onset, longer illness duration, and treatment resistance.

- **Seasonal patterns**: Some individuals show predictable seasonal variations, with depression more common in winter months and mania or hypomania more frequent in spring or summer, possibly related to light exposure and circadian mechanisms.

Common Challenges in Diagnosing Bipolar Disorder Symptoms

Achieving an accurate diagnosis of bipolar disorder presents substantial challenges that contribute to the lengthy diagnostic delays many patients experience. Several factors complicate the recognition of bipolar symptoms, from the nature of the condition itself to limitations in current diagnostic methods. Understanding these challenges illuminates why improved awareness and systematic assessment are so crucial. The most fundamental diagnostic obstacle is that individuals typically seek help during depressive episodes rather than manic or hypomanic ones.

During elevated mood states, people often feel better than baseline””more productive, creative, confident, and energetic. They may not recognize these periods as problematic or may actively enjoy them. Without a clear history of elevated episodes, clinicians may reasonably diagnose major depressive disorder and prescribe antidepressant monotherapy, which can actually destabilize bipolar disorder by triggering manic episodes or accelerating cycling. Obtaining collateral history from family members who have observed the patient across different mood states becomes essential.

- **Comorbidity confounds**: Bipolar disorder frequently co-occurs with anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, substance use disorders, and personality disorders. These overlapping conditions can mask bipolar symptoms or be mistaken for them, complicating diagnostic clarity.

- **Spectrum considerations**: Mood exists on a continuum, and the boundaries between normal mood variation, temperament, cyclothymia, and full bipolar disorder are not always clear-cut. Some individuals show subthreshold symptoms that cause impairment without meeting formal diagnostic criteria.

- **Age-related presentations**: Bipolar disorder manifests differently across the lifespan. In adolescents, irritability and rapid mood shifts may predominate over classic euphoric mania. In older adults, mixed features and cognitive symptoms may be more prominent than in younger patients.

The Relationship Between Bipolar Disorder Symptoms and Cognitive Function

Beyond mood symptoms, bipolar disorder significantly impacts cognitive function in ways that persist even between acute episodes. Neuropsychological research has documented deficits in attention, processing speed, verbal memory, and executive function among individuals with bipolar disorder. These cognitive symptoms often prove more disabling for daily functioning than mood symptoms themselves, affecting work performance, academic achievement, and independent living skills. During mood episodes, cognitive changes are pronounced and state-dependent.

Manic episodes bring distractibility, poor judgment, and impaired ability to assess consequences of actions. Depressive episodes involve slowed thinking, difficulty concentrating, and problems with memory retrieval. Between episodes, many individuals continue to experience subtle but measurable cognitive deficits, particularly in attention and executive function domains. The cumulative effect of multiple mood episodes appears to worsen these deficits over time, providing another compelling reason for consistent treatment and episode prevention. Some emerging evidence suggests that certain treatments, particularly lithium, may have neuroprotective effects that could help preserve cognitive function.

How to Prepare

- **Document mood patterns systematically**: For at least two to four weeks before your appointment, track daily mood states, energy levels, sleep duration and quality, and notable behaviors. Use a numerical scale or mood tracking app to quantify changes. Note any triggers or life events that preceded shifts. This mood diary provides objective data that complements retrospective recall.

- **Compile a comprehensive psychiatric history**: Write down all previous mental health diagnoses, treatments tried, medications prescribed (including dosages and duration), and your response to each treatment. Document any psychiatric hospitalizations, emergency visits, or crisis interventions. Include information about therapy approaches and whether they helped.

- **Gather family mental health information**: Create a family tree noting any relatives with mood disorders, suicide, substance abuse, psychiatric hospitalization, or “nervous breakdowns.” Bipolar disorder has strong genetic components, and family history provides important diagnostic clues. Include information about both sides of the family extending to grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins if possible.

- **Identify collateral informants**: Ask a close family member, partner, or longtime friend who has observed you across different periods if they would be willing to provide information to your clinician. They can describe behavioral changes they have noticed, particularly during potential manic or hypomanic periods that you may not recall clearly or may have viewed positively.

- **Prepare specific examples of concerning behaviors**: Write concrete descriptions of episodes that worried you or others. Include approximate timing, duration, and specific behaviors. For example, rather than “I felt really energetic,” describe “In March, I slept only two hours nightly for a week, started three business ventures, and spent four thousand dollars on equipment for a hobby I abandoned.”

How to Apply This

- **Establish medication adherence routines**: Take medications exactly as prescribed at consistent times daily. Use pill organizers, phone alarms, or apps to support adherence. Never stop or adjust medications without consulting your prescriber, even when feeling well””this is when risk of discontinuation is highest. Understand that mood stabilizers work preventively, and stopping them removes protection against future episodes.

- **Prioritize sleep hygiene as a therapeutic intervention**: Maintain consistent sleep and wake times seven days per week, varying by no more than one hour even on weekends. Create a sleep environment that is dark, quiet, and cool. Avoid caffeine after noon and limit alcohol, which disrupts sleep architecture. Recognize that sleep disruption can trigger episodes and treat insomnia or schedule disruption as urgent concerns requiring clinical attention.

- **Build a monitoring and support network**: Identify two or three trusted individuals who can provide honest feedback about your mood state and behavior. Develop a shared language for discussing observations without judgment. Create a written action plan specifying what steps to take if early warning signs of either pole appear, including emergency contacts and when to seek immediate care.

- **Develop personalized trigger awareness**: Through mood tracking and reflection, identify your specific episode triggers””these commonly include sleep disruption, major life stress, substance use, seasonal changes, or interpersonal conflict. Create strategies to manage unavoidable triggers and eliminate avoidable ones. Share this trigger list with treatment providers and support network members.

Expert Tips

- **Recognize prodromal symptoms early**: Most individuals develop consistent early warning signs before full episodes emerge. Common prodromal symptoms for mania include decreased sleep need, increased energy, rapid speech, or starting multiple projects. For depression, subtle social withdrawal, difficulty with morning routine, or loss of interest in one specific activity may precede the full syndrome. Intervening during prodromal phases can sometimes prevent full episode development.

- **Maintain treatment during stable periods**: The temptation to reduce or stop treatment when feeling well is understandable but dangerous. Bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition requiring ongoing management. Studies consistently show that maintenance treatment dramatically reduces relapse rates. Discuss any concerns about side effects or medication burden with your prescriber rather than making unilateral changes.

- **Be cautious with antidepressants**: Antidepressant medications can destabilize bipolar disorder by triggering manic episodes or accelerating cycling. If you have bipolar disorder and require antidepressant treatment, it should typically be combined with a mood stabilizer and monitored carefully. Never take antidepressants prescribed by a provider unaware of your bipolar diagnosis.

- **Create structure during depressive episodes**: When depression makes initiative feel impossible, external structure provides scaffolding. Schedule essential activities and treat appointments as non-negotiable. Use behavioral activation principles””engage in activities regardless of mood rather than waiting to “feel like it.” Small accomplishments build momentum.

- **Plan for emergencies in advance**: When acutely ill, judgment is compromised and decision-making capacity diminishes. Create a psychiatric advance directive during stable periods that specifies your treatment preferences, authorized decision-makers, and preferred hospitals or providers. Share this document with your treatment team and family members.

Conclusion

Bipolar disorder stands among the most significant mood conditions affecting human brain function, demanding attention from anyone invested in understanding mental health and neurological wellness. The condition’s hallmark symptom pattern””cycles of elevated and depressed mood states with intervening periods of stability””arises from complex neurobiological mechanisms involving genetic vulnerability, neurotransmitter dysregulation, and structural brain changes. Recognizing the full spectrum of bipolar symptoms, from the grandiosity and decreased sleep need of mania through the leaden fatigue and hopelessness of depression, enables earlier diagnosis and more effective intervention. The various subtypes of bipolar disorder, different developmental presentations, and frequent comorbidities add complexity that explains why diagnostic delays remain common despite our advancing knowledge.

For those living with bipolar disorder symptoms or supporting someone who does, the path forward involves partnership with qualified mental health professionals, commitment to comprehensive treatment including medication and psychotherapy, and lifestyle modifications that support stability. The condition is chronic but manageable, and many individuals with bipolar disorder lead rich, productive lives when properly supported. Advances in neuroscience continue to deepen our understanding of the brain mechanisms involved, promising improved treatments in coming years. Whether you are seeking information for yourself, a loved one, or professional development, understanding what bipolar disorder is and how its symptoms manifest represents an essential foundation for reducing stigma, improving outcomes, and supporting brain health.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it typically take to see results?

Results vary depending on individual circumstances, but most people begin to see meaningful progress within 4-8 weeks of consistent effort. Patience and persistence are key factors in achieving lasting outcomes.

Is this approach suitable for beginners?

Yes, this approach works well for beginners when implemented gradually. Starting with the fundamentals and building up over time leads to better long-term results than trying to do everything at once.

What are the most common mistakes to avoid?

The most common mistakes include rushing the process, skipping foundational steps, and failing to track progress. Taking a methodical approach and learning from both successes and setbacks leads to better outcomes.

How can I measure my progress effectively?

Set specific, measurable goals at the outset and track relevant metrics regularly. Keep a journal or log to document your journey, and periodically review your progress against your initial objectives.

When should I seek professional help?

Consider consulting a professional if you encounter persistent challenges, need specialized expertise, or want to accelerate your progress. Professional guidance can provide valuable insights and help you avoid costly mistakes.

What resources do you recommend for further learning?

Look for reputable sources in the field, including industry publications, expert blogs, and educational courses. Joining communities of practitioners can also provide valuable peer support and knowledge sharing.